Mapping out the tribes of climate

November 30, 2022

Climate is a gravity well for talent, but why don’t other, equally impactful topics attract talent in the same way? Why isn’t everyone dropping everything to work on homelessness, or global poverty, or curing cancer? With many peers in tech now working on climate issues, I tried to understand why this topic holds such purchase for so many people – and its incredible staying power over the decades.

Initially, I started with the idea that climate was an attractive industry for “doomer” types, and I painted their motivations monolithically. I was searching for the one weird reason that was causing hordes of people to drop what they were doing and march, hypnotically, towards the same problem space.

What I found instead is that while the media still portrays climate as a simple question of beliefs, the climate field has long moved on to diversified solutions. Whether one believes in climate change is no longer the interesting question; now it’s “What do you think is the right approach?”

Pass through the asteroid belt of climate doomerism, and the universe expands into a rich panoply of different climate tribes. People who work in and around climate don’t all believe the same things. Instead, they inhabit a parallel, mirror world that looks a lot like the non-climate world. Just like in the regular world, there are factions, politics, and competing belief systems.

For example, I did not find that people who are interested in climate fall cleanly along a certain political line of thinking, or even a shared set of values or goals. Climate is frequently coded as a left-leaning issue, but there are also centrist and right-leaning people who operate in different factions.

Nor do climate people all agree on the right solutions to pursue. In some cases, they believe other tribes are actively harmful to their cause. The enemy, in their minds, aren’t climate deniers, as we might have seen a decade or two ago – they’re other people working in climate.

For someone who doesn’t work in climate, trying to figure out which opportunities to pursue – carbon removal, renewables, energy storage and transmission – is a dizzying array of options, with no way to sort or rank their importance. But it seems to me that climate is better understood not as a singular list of technology and policy action items, but as an assortment of climate tribes. Tribes tell us why these opportunities are interesting and help us make better predictions about how they will unfold.

To understand climate better, I slurped up hundreds of thousands of words’ worth of blog posts, podcasts, interviews, articles, and tweets (my notes alone are over 80,000 words) – paying less attention to object-level discussions, and more to the rhetoric being used to describe one’s goals and motivations. I looked for cleavages between values, language and narratives. I then followed up this research with a handful of conversations with those who work in climate, across different tribes, to further refine and “stress test” my characterizations.

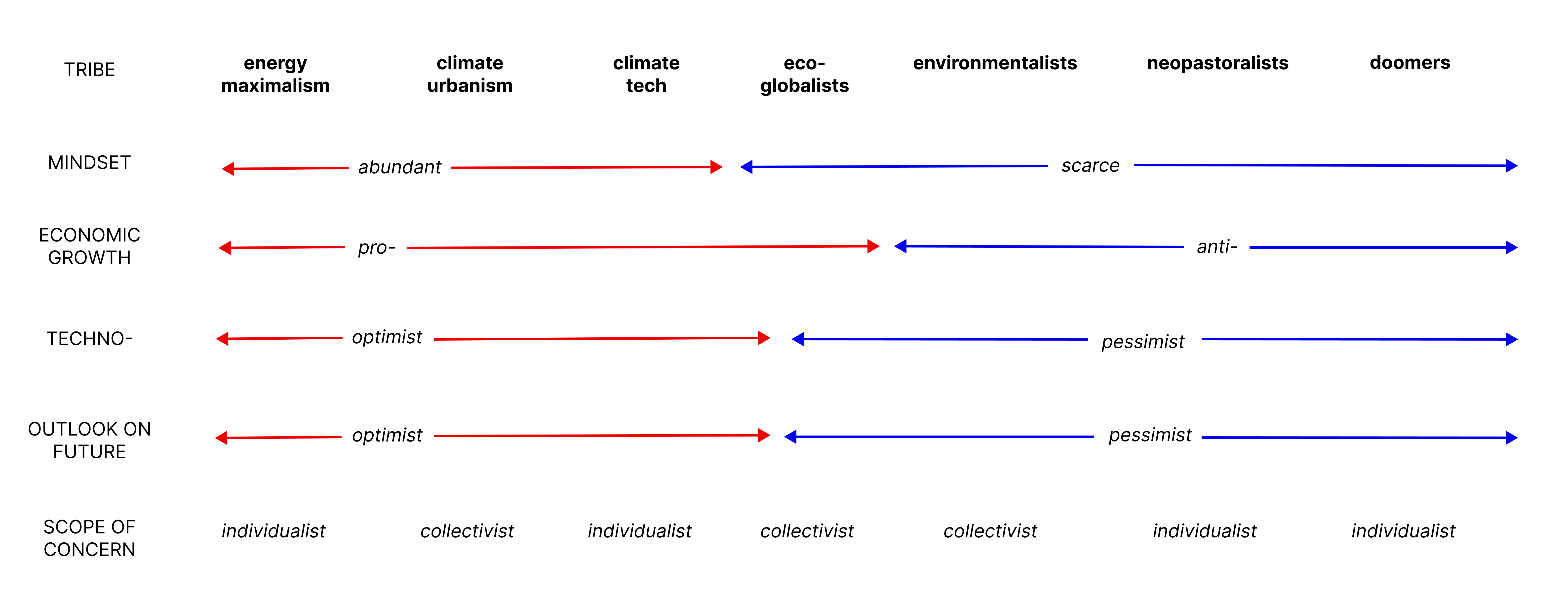

Ultimately, I landed upon seven climate tribes, which I’ll expand on in a bit:

Images generated with DALL-E.

Images generated with DALL-E.

Climate is a huge topic, and there are, of course, many more subcultures that are not fully captured above. (I’ll also add a requisite note that this analysis is heavily centered on American climate trends.) But if you’re a stranger in a strange land who’s trying to figure out what’s going on in climate, I found that grokking these seven groups gave me the conversational fluency to understand most of the climate discourse.

If you just want to read about these climate tribes, you can skip ahead to that section. But if you want to suffer through my process with me, I’ll unpack how I got from an outsider’s view of perceiving climate as a doomer topic, to instead understanding it as a pluralistic landscape of tribes that largely mirrors the non-climate universe in its richness and diversity. We’ll start with the outside layers and work our way in. Licking the Tootsie Pop, so to speak. Here we go.

Table of Contents

- Climate change isn’t about evangelism anymore

- People who work in doomer industries aren’t doomers!

- The climate tribes of today

- Okay, but really - which is the best climate tribe?

- Addendum: ‘Doomer industries’ and the search for meaningful work

Climate change isn’t about evangelism anymore

Over the last four decades, climate has crossed an arc from science to evangelism to tribalism, with each of today’s tribes focused on pushing forward their own solutions.

In the 1980s, climate change (then referred to as global warming) received little attention outside of scientific communities. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations working group that publishes its widely-read reports, was established in 1988 to track and summarize research on the risks and impacts of climate change.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, climate change began to escape from scientific communities into the public domain, though with some bemusement and skepticism. The former vice president Al Gore memorably embarked upon an evangelist’s journey to educate the public about global warming, giving his presentation about climate risk – captured in the 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth – over 1,000 times.

The documentary had a profound impact on John Doerr, who, along with his venture capital firm, Kleiner Perkins, became the face of the cleantech movement in the early 2000s. Doerr gave a TED talk in 2007 titled “Salvation (and profit) in greentech”, where he advocated for reducing energy consumption and regulating emissions through policy.

Al Gore transformed from laughingstock (“ManBearPig”, 2006) to hero (“Time to Get Cereal”, 2018) on South Park, reflecting a change in public sentiment. (Images: IMDB and Fandom)

Al Gore transformed from laughingstock (“ManBearPig”, 2006) to hero (“Time to Get Cereal”, 2018) on South Park, reflecting a change in public sentiment. (Images: IMDB and Fandom)

At the time, the messages from climate evangelists like Gore and Doerr were less sophisticated about solutions and more about getting people to care about global warming in the first place. This was a sensible approach at the time, given that climate advocates were in “recruitment” mode, and public sentiment was still fairly neutral and disengaged.

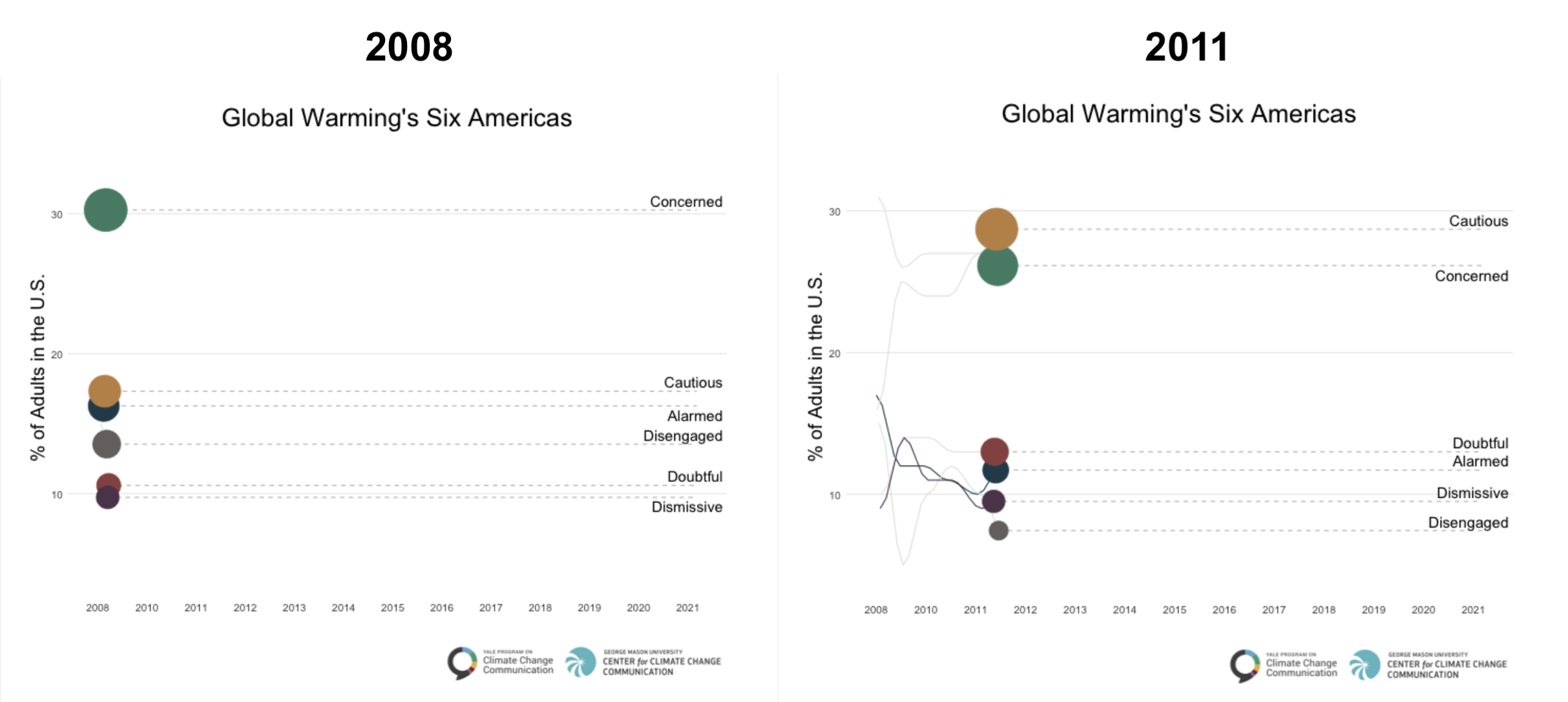

Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communications (YPCCC), which has tracked public attitudes towards climate change for more than a decade, found that roughly 30% of those surveyed in 2008 were “Concerned” about climate change. By 2011, after the cleantech bubble burst, that figure dropped to about 25%, with a larger cohort saying they felt “Cautious” (meaning: undecided) about climate change.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Today, however, it’s safe to say that climate change has won the battle for mindshare. Slip on a pair of augmented reality glasses, and you’ll see the climate universe appear before your eyes. As of 2021, climate tech accounts for 14 cents of every venture capital dollar. ESG assets were worth $37.8 trillion at the end of 2020, and are projected to account for more than one-third of global AUM by 2025. Climate fiction, or “cli-fi,” is an emerging genre of fiction that is focused on climate change. Climate is one of the most popular categories among Substack writers. “Eco-therapy” is a field of therapy that helps patients work through their feelings of anxiety and depression about climate change. One in four childless American adults say that climate change has influenced whether they will have children or not.

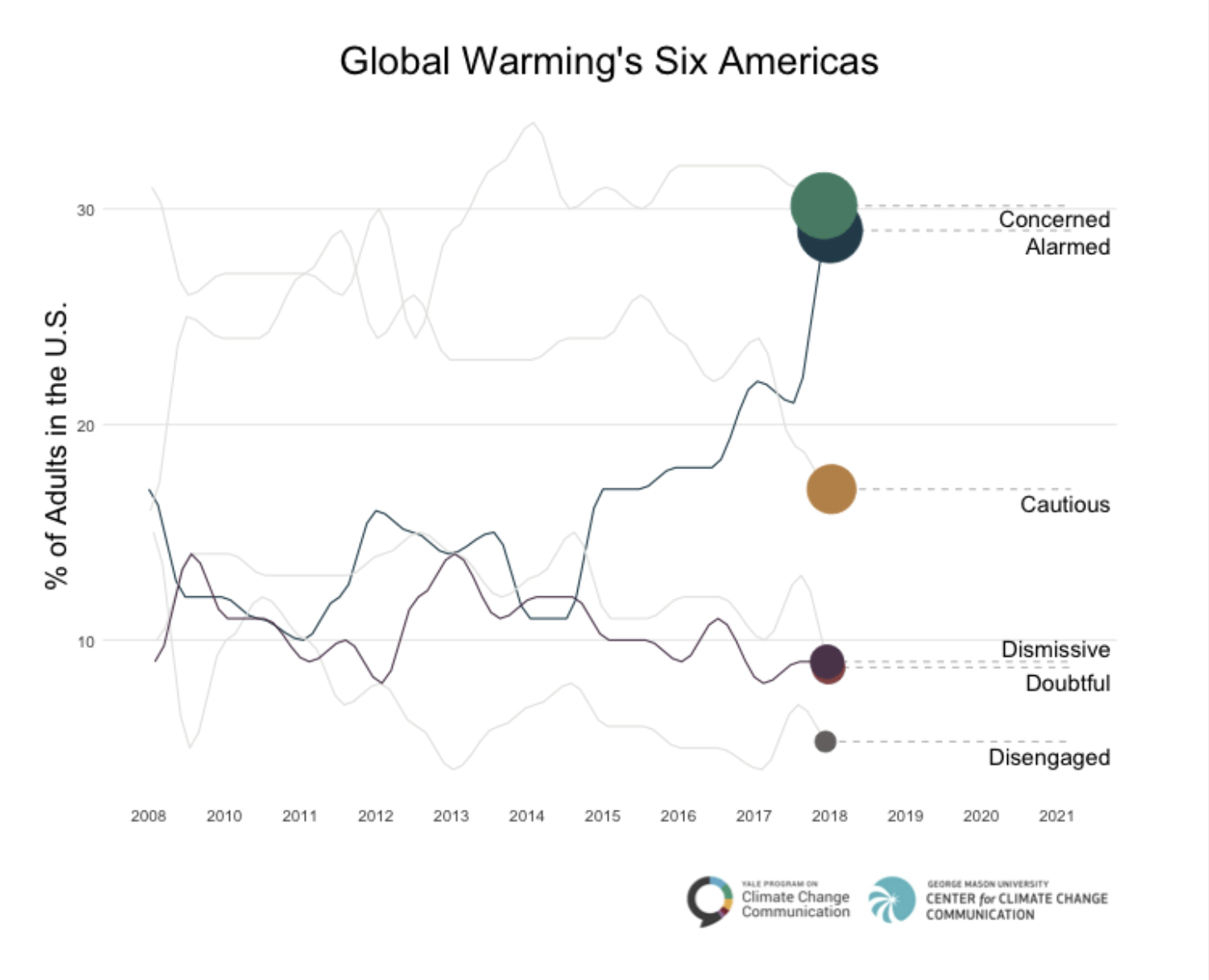

2018 seems to have been the magical year that the climate narrative flipped, driven in part by an IPCC special report that described the impacts of 1.5°C global warming to the public. According to YPCCC, the most concerned category (“Alarmed”) grew sharply starting in 2018, nearly doubling from 18% in 2017 to 33% of American adults surveyed in 2021. The term “doomer” also became popular starting in 2018, thanks to a popular 4chan meme.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Most of this change in public sentiment appears to come from converting the “Concerned” and “Cautious” groups to “Alarmed”, rather than the disinterested groups, which remained roughly unchanged. In other words, people who were already somewhat concerned about climate in previous years became more extreme in their views. [1]

Climate change has now progressed beyond an early evangelism phase and into the solutions phase. Despite this development, however, media coverage about climate lags behind, continuing to shoehorn climate into a sensationalized, binary question of beliefs, rather than focusing on the more nuanced set of attitudes that drive climate action.

In the early 2000s, “climate critics” were those who questioned whether global warming was real at all. The late author Michael Crichton delivered a series of eloquent talks about environmentalism and religion. Crichton, who studied anthropology in college, argued that environmentalism had become a personal source of meaning for people, which prevented them from being able to objectively evaluate climate risk according to science.

But today, even self-proclaimed environmentalists openly criticize the climate doomer narrative. Michael Shellenberger, who co-founded environmental research center Breakthrough Institute, published a book in 2020 called Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All, where he questioned the value of climate doomerism and the psychological toll it takes on us. In response, The Guardian – one of the most prominent mainstream outlets covering climate change – called Shellenberger and Bjorn Lomborg (who wrote a book with a similar thesis) “lukewarmers,” claiming that they “take climate science denial to another level.” Similarly, Heated writer Emily Atkin called the recent “anti-ESG” movement a “climate denial movement,” rather than an objection to the specific strategy of portfolio management as an effective means of addressing climate change.

To be fair, the critics willingly play into this narrative, too. Like Crichton, Shellenberger stubbornly advocates that we “separate science from fiction” when discussing climate and focus on the facts. I share the sentiments of both Crichton and Shellenberger regarding the value of doomer narratives, but I also wonder whether the “science versus religion” narrative is still relevant in today’s landscape. [2] Crichton himself stated that he thinks “you cannot eliminate religion from the psyche of mankind. If you suppress it in one form, it merely re-emerges in another form.”

If religious tendencies cannot be repressed from our collective psyches, why not start with the premise that climate is a religion, then try to understand it on those terms? Instead of insisting that we “stick to science” or only focus on technology, we can instead evaluate climate opportunities through the lens of tribal values.

People who work in doomer industries aren’t doomers!

It’d be nice and tidy for us (and a much shorter blog post) if we could simply declare the post-2018 rise of doomerism to be the cause of people suddenly leaving their jobs to work in climate. Unfortunately, this oversimplified narrative starts to break down once we actually evaluate people’s motivations for working in climate, versus general public sentiment.

Doomerism only takes us to the edge of the climate universe. Once inside, I noticed that there was very little doomer talk amongst people who actually work in climate. If anything, they seemed quite optimistic. This makes sense if you think about it: why would you work in a doomer industry if you thought there was no hope?

We can validate this mindset by comparing climate to a parallel doomer industry. Anders Sandberg, who researches global catastrophic risk, once remarked that:

Yesterday, when a friend heard I worked on the end of the world I was asked what I thought about the imminent social collapse. I was confused: “why do you think there is one?”

He added, thoughtfully:

The funny thing with the conversation yesterday was that the two of us working on xrisk were pretty optimistic (but thinking that the risks were real and worth working hard on), while the non-xrisk people were gloomy.

In climate, Hannah Ritchie, a data scientist at Our World in Data, makes a similar observation to Anders: “In reality, it is possible to solve our environmental problems. Climate scientists certainly think so. They are often less pessimistic than the general public, which is a new and odd disconnect.”

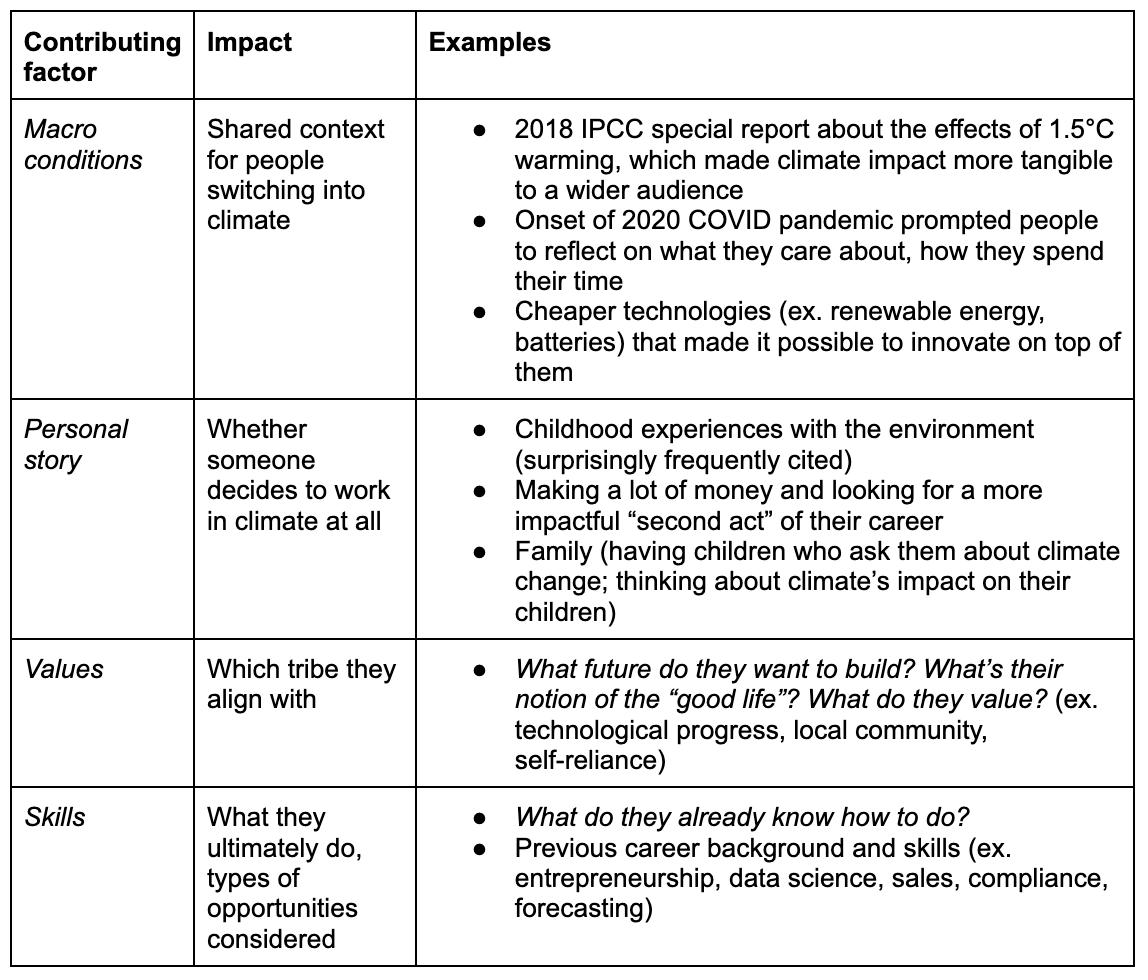

If people who work in climate aren’t doomers, I tried to figure out how they ended up there instead. What were their career backgrounds, skills, interests? I drew upon a combination of public interviews [3], as well as private conversations, to understand this question.

When it comes to working in climate, I noticed two major personas:

- Incumbents: People with specialized skills who have been working in relevant industries for awhile (ex. scientists, policy researchers, or those who work in e.g. energy, utilities, manufacturing, agriculture)

- Switchers: People with generalized skills who switched into climate (frequently those with a background in tech, finance, management consulting, or corporate executives)

Climate incumbents are more likely to be driven by personal curiosity. They have specialized skills and interests that just so happen to coincide with a very big trend. This group is more or less disinterested in the mainstream climate discourse, although they’re glad it means there is more funding and talent available. They rarely allude to the climate crisis at all (with the exception of, e.g. climate scientists turned public advocates), instead focusing on their personal excitement at being able to solve a specific problem.

For example, Gaurab Chakrabarti, co-founder of Solugen, a company that produces chemicals from plant-based alternatives, explained, “It wasn’t supposed to be a company…we were just passionate about the science…and what we decided at that point was well, if this is working at…a scientific level, is there relevance to society for this?”

John Dees, an analyst at Carbon Direct with a background in GIS who now focuses on lifecycle assessments for carbon emissions, only became aware of the broader climate crisis later on:

I would say the anxiety is more nascent. I think for me initially, just because the way my brain works, it seemed like a challenge and a problem to be solved….I was looking at individual technologies that potentially have an impact, but it took a while to situate that into larger conversations about energy systems and think about the big picture.

Climate switchers, on the other hand, usually don’t have backgrounds in anything climate-related (a fact that many are comfortable with, and sometimes even poke fun at themselves about). They’re “problem solving” types who are deeply bought into a certain worldview that made them successful in the first act of their careers, and they’re now pursuing climate as a second act. Many explicitly state that climate is a way to do something “more impactful” with their careers, which provides them with deeper meaning than, say, managing employees at a Fortune 500 company or selling SaaS products.

For example, Jason Jacobs, who founded Runkeeper and sold it to Asics, initially “talked [himself] into trying to build another consumer company,” but quickly realized that “the purpose element was really lacking for me.”

Caroline Klatt, who previously worked at Fab and co-founded and sold Headliner Labs, an enterprise solution for retail companies, said that, “We had a really rewarding experience with our first company and certainly felt like…if we did this again…it should be something with…real world impact that was measurable and that we can look back and feel really proud about the impact we had on the world.”

Climate switchers are attracted to problems they know how to fix: they will often apply their existing skills, such as data engineering or compliance, towards climate, rather than acquire new skills.

Rachel Delacour, for example, who sold her business intelligence startup to Zendesk before starting carbon accounting company Sweep, said that despite being concerned about climate, she realized she “couldn’t go back [to] university, spend time to ramp up, become a scientific chemist.” Instead, she and her co-founders asked themselves, “How can we do our part?…What were our skill sets?”, ultimately repurposing their business intelligence and entrepreneurial skills towards climate.

The strategies pursued by climate switchers are informed by their professional backgrounds and what they’ve seen work in their careers, which ultimately leads to the formation of different climate tribes. Climate tech types, for example, might look for unexplored technology gaps to commercialize, whereas eco-globalist types will focus more on regulation and measuring risk.

Here are some of the major motivating factors that were self-reported by climate switchers:

Self-reported motivations for switching into climate work from a different industry.

Self-reported motivations for switching into climate work from a different industry.

Returning to my Tootsie pop metaphor, we can see that a superficial “doomer” narrative only refers to the hard candy exterior, but there’s actually a lot more going on under the surface. If we were to organize the climate industry, based on motivations and interests, it might look something like this:

Mr. Owl does not endorse this diagram.

Mr. Owl does not endorse this diagram.

- Bright, sugary exterior: Climate doomerism, largely driven by media, the doomer climate tribe, and outsiders who don’t work in climate.

- Surprisingly substantive, dense interior: This is where much of the climate work gets done, driven by different tribes. Each tribe has its own values and strategies, but all are generally preoccupied with realizing a vision of the future outside of themselves.

- Hard stick in the very center: Not very tasty, but a necessary and oft-unappreciated foundation. This group would work in climate regardless of its trendiness: those with science backgrounds, or in relevant industries like energy or manufacturing. They’re motivated by personal curiosity and desire to solve an (often technical) problem.

Like any talent ecosystem, these groups are symbiotically connected. Doomerism serves a general PR purpose, even if it’s annoying. It keeps what might otherwise be a niche academic or business endeavor in the public’s top of mind. Without doomerism, growing artificial meat or building an algae farm to capture carbon might be just another scientist’s crazy pet project, struggling for funding. Similarly, climate tribes need scientists to balance their business and policy skills, while science types need people who are willing and able to commercialize technology and communicate with the general public.

Now that we’ve covered the general motivations of people who work in climate, let’s take a closer look at the climate tribes. What do different tribes care about, and what sorts of agendas do they pursue?

The climate tribes of today

Here are seven tribes that are influencing climate work today. They are very loosely organized from the center (or “lollipop stick,” if you will), radiating outwards towards doomerism, but I wouldn’t focus too much on the ranking.

Also note that the people, orgs, and keywords mentioned here are non-comprehensive lists – think of them more as assorted ephemera, meant to evoke the aesthetic of that tribe. If you have ideas for other names to include for any of these tribes, or think something has been miscategorized, please drop me a line or DM me on Twitter, I’d love to hear it!

Energy maximalism

Instead of trying to limit consumption, energy maximalists envision a world in which energy is no longer a limiting resource. Their goal is to develop technology and policy that makes it possible to have endless energy. (It is notable that this group uses the term “energy” and seems to avoid the term “climate.”)

This summer, Eli Dourado and Austin Vernon published a paper called “Energy Superabundance: How Cheap, Abundant Energy Will Shape Our Future,” where they argue that energy abundance is directly correlated to economic growth, and that industry and policy have been overly focused on limiting rather than unlocking more energy.

Many people in this tribe are affiliated with ecomodernism, an umbrella philosophy that takes an anthropocentric view of the environment. (Several other tribes on this list would also be considered ecomodernist.) Breakthrough Institute, which was founded in 2007, is an organization affiliated with both ecomodernism and energy maximalism.

While many energy maximalists support nuclear as part of a broader energy portfolio, a subset could be called nuclear maximalists: those who believe that nuclear is the best, and ideally primary, form of energy (ex. Michael Shellenberger, Isabelle Boemeke).

Snapshot

- Pro-economic growth

- Techno-optimist

- Individualist

- Optimistic about the future

- Abundance mindset

- Related movements: Ecomodernism

- Areas of interest: Nuclear, geothermal, pro-energy policy

- Relevant people and orgs: Eli Dourado, Austin Vernon, Mark Nelson, Breakthrough Institute, Tim Latimer, Michael Shellenberger, Isabelle Boemeke

- Keywords: energy, abundance, growth, nuclear

Climate urbanism

Climate urbanists envision a densely populated world that’s harmoniously networked, industrious, and resilient to climate threats. Cities are the primary leverage point for their solutions, reflecting both a global trend towards urbanization, as well as providing the best “bang for your buck” of being able to experiment with climate solutions that can impact millions. Cities can also operate somewhat independently from state and federal governance, which can make it easier to enact changes.

It’s hard to know where exactly “urbanism” stops and “climate urbanism” begins, and I debated whether this should be its own tribe at all, as urbanism is motivated by much more than just climate. Nevertheless, many urbanist initiatives are also climate initiatives, and some urbanists explicitly invoke climate motivations when discussing their work. Eric Quidenus-Wahlforss, who previously co-founded SoundCloud and now started Dance, an e-bike subscription startup, explains his mission as “accelerating the transformation of cities and just making cities more livable and shifting the mix of cars in cities…and I think if many cities transform like that, it’s a very meaningful impact on climate.”

Lyn Stoler and Sonam Velani recently introduced the term “climate industrialism”, which they describe as an “optimistic, action-oriented response.” Like energy maximalists, they believe climate solutions are directly correlated with economic growth and “[reject] the idea that climate solutions have to be rooted in scarcity and sacrifice. Instead, it’s a bet that climate solutions rooted in abundance and progress can and will create value for people in their daily lives, homes, communities, and cities.” Unlike energy maximalists, climate urbanists are more collective- than individual-oriented – hence the focus on urban environments.

Snapshot

- Pro-economic growth

- Techno-optimist

- Collectivist

- Optimistic about the future

- Abundance mindset

- Related movements: Urbanism, solarpunk

- Areas of interest: Infrastructure, transportation, construction, energy transmission, climate adaptation, renewable energy

- Relevant people and orgs: Ezra Klein, Jesse Jenkins, Lyn Stoler, YIMBY, 2150.vc

- Keywords: cities, progress, infrastructure, optimism, housing, resilience

Climate tech

Those in climate tech bring a “disruptor’s mindset” to climate. They can be characterized as mildly reactionary to the eco-globalists, believing that the last two decades of global negotiations have little to show for, and that we can instead move faster and more efficiently through the early-stage private sector – primarily, startups. Some in climate tech still have battle scars from the early 2000s cleantech bubble, but enough time has passed that a new generation is willing to learn from previous lessons and experiment with new opportunities.

Those in climate tech see policy as a means of unlocking innovation, rather than as a primary tool for change. The goal is to remove policy roadblocks, not add more (see, for example, the Institute for Progress’s paper on National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reform, which argues that the environmental review process is “slowing down the clean energy transition”). Instead, they focus on innovating through commercial markets.

Chris Sacca, for example, is not unlike John Doerr in some ways: they are both charismatic venture capitalists who believe in investing in the future of climate technology. But whereas Doerr still believes policy and regulation are a key part of that strategy, Sacca states that: “The reality is, I hate politics….For a startup person, all those layers are maddening. We are used to seeing a problem, building something we think helps, and then giving it directly to users and buyers….Counting on our leaders to really make the scale of changes we need is an exercise in futility.”

While energy maximalists skew more towards the R&D side of technology, climate tech operates more on the commercial side of the pipeline: bringing existing technologies to market. Those in climate tech are always looking for low-hanging fruit, overlooked gaps and points of leverage. The carbon removal initiative Frontier, for example, released a “carbon removal (CDR) gap database”, highlighting major knowledge and innovation barriers to carbon removal.

Climate technologists are also less opinionated about climate’s influence on culture or lifestyle (beyond startups-as-an-ideology); to them, climate is more of an operational and commercialization issue.

Snapshot

- Pro-economic growth

- Techno-optimist

- Individualist

- Abundance mindset

- Neutral to optimistic about the future (this group tends to be more anxious and focused on downsides, but they generally believe we can solve these problems)

- Areas of interest: Carbon removal, energy storage, renewables, policy reform, nuclear, geoengineering

- Relevant people and orgs: Stripe Climate, Frontier, Nan Ransohoff, Shayle Kann, Lowercarbon Capital, Chris Sacca, Ryan Orbuch, Jason Jacobs, Climate Tech VC

- Keywords: scale, decarbonization, removing roadblocks, progress, building, innovation

Eco-globalism

This group is focused on regulation as the primary vehicle of change, with the goal of reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Unlike the aforementioned tribes, eco-globalists take a scarcity approach to climate. As they see it, we only have a finite set of resources, and the major task is to figure out how to allocate them efficiently. This mindset naturally puts the focus on regulation – whether literally (ex. policymaking) or figuratively (ex. tracking and measurement). Whereas climate technologists see regulation as a way to remove roadblocks, eco-globalists see regulation as a way to enforce behavior.

While those in climate tech are more likely to have a background in startups, eco-globalists are more likely to have a background in finance or management consulting. But there are exceptions: John Doerr favors investing in and developing new technology, but his thinking is unmistakably eco-globalist. Doerr’s most recent book, Speed and Scale, proposes an action plan modeled after the OKR accountability system. Each section of the scorecard identifies a target to meet, such as “Remove 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year from the atmosphere.” Similarly, climate solutions like Watershed and Patch could be classified as eco-globalist, despite being startups, because they are enterprise platforms focused on climate accounting.

Eco-globalists are comfortable with the business sector; they believe climate solutions don’t have to come at the expense of financial returns. However, they’re more focused on making an impact via public corporations (ex. ESG investing), whereas climate technologists focus on startups.

Snapshot

- Pro-economic growth

- Tech-neutral

- Collectivist

- Scarcity mindset

- Neutral about the future (they still think it’s possible to fix climate change, but are much more alarmed)

- Interests: carbon offsets and credits; carbon pricing; carbon tax; setting and enforcing emission targets; energy efficiency; reducing consumption; Green New Deal; ESG investing; global climate impact; renewables

- Relevant people and orgs: World Economic Forum, UN Climate Change Conference (COPx), Bloomberg Green, Tom Steyer, John Doerr

- Keywords: sustainability, reporting, targets, efficiency, supply chain, climate crisis, climate action

Environmentalism

The environmentalists are the anti-corporate counterpart to the eco-globalists, and the modern descendants of “classic” environmentalism that dominated the second half of the 20th century (more on that in a bit). Like eco-globalists, environmentalists focus on sustainability as the ideal outcome, but they’re more concerned with the impact of individual (rather than collective) actions, whether that’s holding Exxon accountable or reducing personal energy consumption. They blame the fossil fuel industry for our climate problems, and believe that corporate lobbying efforts are hindering progress today.

Within environmentalism, there are two further sub-groupings:

- Those focused on climate justice, namely holding others accountable through anti-corporate and political advocacy; and

- Degrowth, which is concerned with finding meaning and impact in focusing on local communities, like towns, neighborhoods, and their own homes.

After much deliberation, I decided these groups belong to the same tribe because they share similar visions, even if their tactics differ. Michael E. Mann, for example, blames fossil fuel companies for the climate crisis in his book The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, while degrowth advocate Samuel Alexander calls for “simple living” as a “desirable alternative to consumer culture,” which he believes will “save our planet from the environmental catastrophe towards which we are so enthusiastically marching.” But both share the premise that a better world is one in which corporate interests take a backseat to sustainable living.

I think of climate justice as a more defensive position (protecting the planet from bad actors), whereas degrowth is a more offensive position (advocating for a new way of thinking about the economy). Despite its branding, degrowthers are not really regressive, from a tactical perspective: they’re actively trying to transition us to a new way of doing things, rather than arguing within the boundaries of our existing paradigm.

Snapshot

- Anti-economic growth

- Techno-pessimist

- Collectivist

- Scarcity mindset

- Pessimistic about the future

- Related movements: classic environmentalism (1960s-1990s), peak oil, environmental justice, climate justice, degrowth

- Interests: political advocacy, anti-corporate lobbying, anti-nuclear, recycling, overpopulation, renewable energy, Green New Deal

- Relevant people and orgs: Sierra Club, Mother Jones, Grist, The Guardian, Hot Take, Assaad Razzouk, Leah Stokes, Mark Ruffalo, HEATED, Jason Hickel, Earthjustice

- Keywords: degrowth, environment, fossil fuels, sustainability, consumerism, carbon footprint, reduce, extractivism

Neopastoralism

Neopastoralists believe that technology has corrupted our natural environment and that society is unraveling, followed by a rewriting of our political and social systems. Like doomers, they feel that the world is changing for the worse, but unlike doomers, they are in the “acceptance” rather than “anger” stage of grief. As the Doomer Optimists put it, it is “an orientation that says: we see the world as it is, and we move forward with a practical, positive vision despite the challenges.”

Neopastoralists believe we need to prepare for the coming transition, but life will go on regardless. They are focused on climate adaptation, but from a self-preservation standpoint. They believe self-reliance is more important than coordinating with others, and prioritize protecting themselves and their loved ones.

(Edit: Jason Snyder, a cofounder of Doomer Optimism, feels this categorization doesn’t adequately capture the nuance of their work. I’ve slightly edited my opening description where I agree my language could be more precise, but otherwise stand by my analysis; however, I’m linking to his response on Twitter here to provide additional color on how Doomer Optimists view themselves.)

Snapshot

- Anti-economic growth

- Techno-pessimist

- Individualist

- Scarcity mindset

- Pessimistic about the future

- Related movements: anarcho-primitivism, retvrn, accelerationism, preppers, Pine Tree gang

- Interests: personal preparedness, farming, homeschooling, regenerative finance, New Urbanism

- Relevant people and orgs: Doomer Optimism, Willow Liana, Anarcho-Contrarian, Industrial Society and Its Future

- Keywords: homesteading, prepping, resilience, adaptation

Doomerism

Doomers believe there is no hope for the future. Like the environmentalists, they are frequently in tension with eco-globalists, whom they perceive as the only tribe capable of saving our planet, and whom they blame for allowing us to fall into a climate crisis from which we can no longer return.

Doomers are largely disconnected from positive-sum climate efforts; their actions are centered around managing their subjective experience of the world. Within this tribe, there are two major sub-types:

- Introspective: focused on managing their emotions amidst external turmoil – Britt Wray, for example, states that activism is “unhelpful” for combatting eco-anxiety

- Externalized: channeling their anger into performative “shock” activism, such as Greta Thunberg, who scolded UN Climate Action Summit attendees in 2019, or Just Stop Oil activists Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, who threw cans of soup on a Van Gogh painting

Doomers see themselves as victims of a climate crisis, and do not feel empowered to stop or otherwise influence the inevitable apocalypse.

Snapshot

- Anti-economic growth

- Techno-pessimist

- Individualist

- Scarcity mindset

- Pessimistic about the future

- Interests: activism, protests, eco-therapy, self-care

- Relevant people and orgs: Greta Thunberg, Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, Gen Dread

- Keywords: (climate, eco-) anxiety, trauma, grief; climate crisis; climate denial; extinction

For a snapshot view, here are all the tribes, plotted along a few key parameters:

Finally, just to round out our landscape, here are a few other groups I considered including, but I think aren’t (yet?) quite full-fledged tribes:

- Climate escapists: People who want to get off the planet and explore new frontiers (ex. Musk, Bezos)

- Regenerative finance (“ReFi”): Those who want to rethink our financial system from the ground up, designing money in a way that regenerates, rather than depletes, our capital assets, using tokenomics and blockchain technology

- Bobrossians: A gentler strain of doomers who believe the world is unsalvageable, but are focused on finding the small wins and joys in life (aka “happy little trees”) – see, for example, the All We Can Save Project

Okay, but really - which is the best climate tribe?

In contrast to 20th-century environmentalism – a largely monolithic social cause – today’s climate world is more like a pluralistic landscape of tribes. Implicit in this reframing is a belief that there is no single “best climate solution” that needs to win out.

There is no shortage of talent, funding, and resources flowing towards climate. Lots of people want to work in climate, and lots of people want to fund it (for now, anyway). If climate is a parallel universe rather than a niche cause area, we ought to lean into the marketplace of ideas and encourage everyone to go work on the solution that speaks to them.

Tribalism is often depicted as a bad thing, especially in the context of climate. Some people claim that such divisiveness politicized climate science; that it brought us to a global stalemate; that climate solutions require us to set aside our differences and work together to resolve an existential threat. I find this framing to be totally unrealistic. There is no unified “we” in climate, any more than there is in the normal world, and pretending otherwise is exactly what keeps us trapped in these failed coordination games.

The idea that we are headed towards an inevitable disaster, or that we must focus our efforts on global negotiations between state actors, are perspectives that belong to specific climate tribes. They don’t speak for everyone, and dissenters should feel free to reject or reshape that language. By the end of this research, I was surprised to find that I actually do have more of a stance on climate than I realized; I just needed to find a tribe that spoke to me.

Why do climate tribes matter? Tribes can help people find each other more quickly by communicating values instead of agendas. “Let’s switch to nuclear energy” doesn’t sound very intriguing to someone who’s not interested in climate at all. “Let’s stop talking about scarcity and instead talk about abundance, starting with our energy needs,” however, might make them perk up their ears. (This rhymes with my conception of idea machines: a modern approach to turning ideas into outcomes by starting with a community, which only develops an agenda downstream of its values.)

Secondly, tribes are a better way of forecasting what the future looks like. By understanding climate efforts as distinct, dynamic networks of talent and funding, driven by a shared set of values, we can better understand the potential of the ideas they advocate for, as well as their risks and shortcomings. To use a simple example, the funding for climate tech versus eco-globalism comes from two very different places. In analyzing the long-term viability of climate work, we ought to consider not just macro conditions that might affect all tribes (such as the price of specific technologies), but also the risks associated with specific funding sources, which might lead one tribe to falter, while another one thrives.

Finally, the most important thing about climate tribes is that they shift the conversation from passive, “true-believer” narratives towards active, action-oriented ones. I couldn’t help but notice that the aforementioned YPCCC climate typology is inherently passive. [4] “How worried are you about climate change?” is a very different question from “What do you believe is the right approach?” Again, this was a reasonable way to categorize public sentiment in 2008, when the goal really was about getting people to care about this topic, but today, we’ve moved past the evangelism phase and into the building phase. One can be “alarmed” about climate change, as a third of American adults apparently are, and not do anything about it. But you can’t be in a climate tribe without having an opinion about solutions.

Addendum: ‘Doomer industries’ and the search for meaningful work

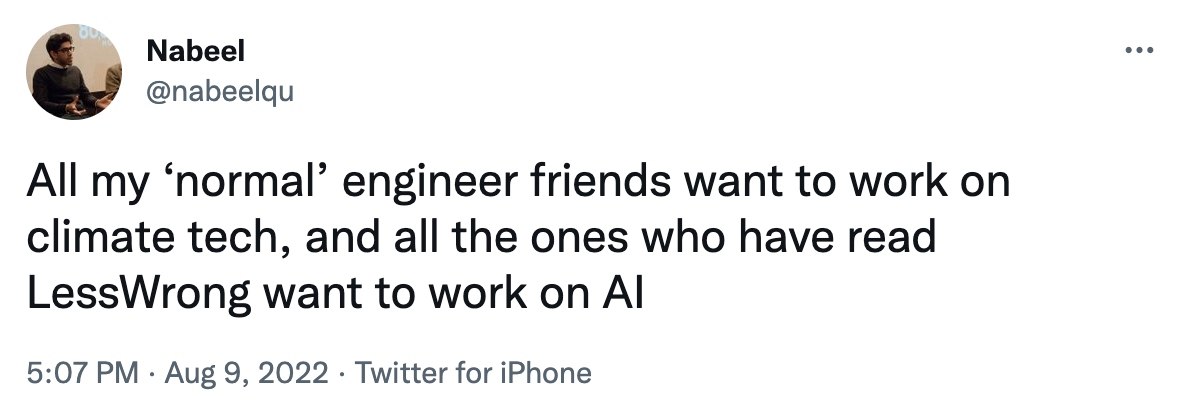

Part of why I was inspired to research and write this piece is because I saw this tweet from Nabeel Qureshi:

…which made me consider climate as part of a bigger category of what I’ve been calling “doomer industries” in my head. A doomer industry is the talent ecosystem that forms around a perceived civilizational threat that demands us to prioritize it, for the sake of humanity, over whatever else we might want to do instead. Doomer industries like climate and AI safety have a sort of wheedling, persistent mind-virus quality to them that other important topics – say, global poverty or education – do not.

Besides climate, a few other examples of doomer industries might include: AI safety, biosecurity, global catastrophic risk, misinformation, and population decline (and its counterpart from a previous generation, overpopulation). And while the human attraction to religious apocalypticism is pervasive (there’s even a name for it: eschatology), doomer industries – as a way of finding meaning in one’s primary work – appear to be a fairly recent development.

In this final section, I thought I’d take a moment to zoom out of climate and ask: is climate’s transformation from “social cause” to “doomer industry” indicative of some broader trend? Will we see speciation of doomer industries? Is there a generalizable shape to these industries, and if so, can other cause areas replicate it to attract more talent and funding? [5]

Let’s start by taking a look at when climate switched from social cause to doomer industry, and why that switch happened. The nuclear advocate and environmentalist Michael Shellenberger posits that climate only took on an apocalyptic pall following two world wars and a Cold War, when we ran out of “real” doomer scenarios to be afraid of:

[T]his whole apocalyptic climate discussion really gained in importance when the apocalyptic nuclear weapons discussion came to an end at the end of the Cold War and so secular fears of apocalypse had to find something else to attach to. Even nuclear weapons was a substitute for earlier apocalypse presentations, including fascism and communism.

The Cold War era does, curiously, coincide with the birth of modern environmentalism in the 1960s and 1970s, which I’ll try to do justice to with just a few paragraphs’ summary:

Prior to the Cold War, environmentalism was seen more as a distinct social movement that one might opt into, rather than as a totalizing force. In the early 20th century, “caring about the environment” was narrowly focused on stewardship of natural resources, culminating in two major, but related, schools of thought – conservationists (such as Teddy Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot) and preservationists (such as John Muir) – that reigned for at least half a century. The establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, along with organizations like the Sierra Club, National Geographic Society, and National Audubon Society, reflected the formalization of these early environmental movements.

By the 1960s, however, environmentalism took on a much more urgent, alarmist tone, with conservationists questioning the effects of a post-WWII society that was newly enamored with mass production. In 1962, the biologist Rachel Carson published her manifesto Silent Spring, which stoked public fear about the harmful effects of pesticides and kicked off a new, advocacy-oriented “Greenpeace generation” of environmentalism that was primarily concerned with the harmful effects of human consumption and economic growth. As a result of these efforts, the EPA was established, along with the first Earth Day, in 1970. The activist era of environmentalism continued for several more decades, becoming more anti-corporate- than regulation-focused over time, including more extreme branches of so-called “radical environmentalism” (such as ecoterrorist organizations ELF and ELA).

Finally, the late 1990s marked a third era of environmentalism, converging on a shared “apocalyptic scenario” with the rising threat of global warming – which brings us to today, where we now see environmentalism decomposing into climate tribes.

From a historical perspective, then, someone like Shellenberger might say that the reason we have doomer industries is because, in a secularized world of comparative peace and prosperity, it fills the role of some primal human need for community. Preventing a doomsday scenario is a way to feel connected to millions of other people, all working towards the same purpose, just as previous generations once felt in rallying around war efforts, or the race to beat the Soviets. Environmentalism is a rare natural fit for this topic compared to other cause areas, because the environment affects everyone – reaching across geographies, socioeconomic class, and demographics.

Still, even in the post-Cold War version of environmentalism, climate didn’t become a widespread doomer topic until 2018, as previously discussed. From, let’s say, the 1960s through the early 2000s, “being an environmentalist” was an identity label that most people did not affiliate with. It was certainly not considered to be part of one’s day job, outside of activists and nonprofit workers.

Unsurprisingly, 2018 coincides with a lot of other trends around political polarization and social media, which we might speculate caused doomer industries to make the leap from being niche cause areas to high-status types of work. I will attempt no further analysis here, as that seems beyond the scope of this (already very long) post, beyond pointing out that the widespread adoption of social media seems to coincide with a growing shift in how we define meaningful work. [6]

So what does a doomer industry look like, exactly? Inspired by Nabeel’s tweet, I tried to model the shape of a doomer industry by looking at the “digital fingerprints” – forums, blog posts, institutional work – of both AI safety and climate in parallel. Here are a few common qualities I noticed:

Shared belief in a disaster scenario

Most obviously, doomer industries require a shared belief in a disaster scenario, which lacks specificity and has no clear date for the “day of reckoning”, but is understood to have a totalizing effect across all aspects of life. (This mentality is what usually attracts pejorative comparisons between doomer industries and religion.)

In the vein of “No one ever fired someone for buying IBM,” the presence of such a scenario makes it easy to justify working on this type of cause area, because “No one can blame me for wanting to save the world from destruction.”

For both climate and AI safety, I was surprised by the lack of consensus as to what, exactly, was going to happen and when, despite popular media portrayals of climate as an extinction-level event (see, for example, the movie Don’t Look Up [7]). The novelist Jonathan Franzen wrote in a widely-shared 2019 essay:

Today, the scientific evidence verges on irrefutable. If you’re younger than sixty, you have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought. If you’re under thirty, you’re all but guaranteed to witness it.

Meanwhile, Hannah Ritchie, the Our World in Data researcher, regards such pronouncements with puzzlement:

[One protestor] told a journalist that the hunger was “nothing compared to what we can expect when the climate crisis unleashes a famine here in Europe in 20 years.” I couldn’t work out where this claim was coming from. Not from scientists. No credible ones have made this claim. Climate change will affect agriculture…but famine across temperate Europe? Within 20 years?

Similarly, in AI safety, Eliezer Yudkowsky, who co-founded the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), which studies artificial general intelligence (AGI), published a cheeky “April Fool’s, but not really” post earlier this year about how MIRI had lost all hope and was pivoting to a “death with dignity” strategy:

It’s obvious at this point that humanity isn’t going to solve the alignment problem…Since survival is unattainable, we should shift the focus of our efforts to helping humanity die with slightly more dignity.

But then there are others on LessWrong who believe AGI is a threat, but not at the level of certainty and precision with which it is discussed. As LW user mukashi explains:

I think that extinction by AI is definitely a possibility….what I most disagree about is their estimate of the likelihood of such an event: most of the discussions I have read are about how doom is just a fait accompli: it is not so much a question of will it take place? but, when? And they are…making a set of predictions that seem bizarrely precise, trying to say how things will happen step by step.

It’s also interesting that both the climate and AGI apocalypses – two cause areas that should be completely unrelated – are thought to be roughly 30 years away. While I don’t think anyone is deliberately fabricating such a scenario, it does seem to reveal something about our underlying collective psychology.

Ten years would be too soon; it would arouse doubts as to the veracity of such a claim, and require immediate action (i.e. calling the hand). Fifty years feels too far away to be relevant. Thirty years, however, is just distant enough that our prediction abilities get fuzzy, but close enough to theoretically impact the lives of every working adult today.

Adjacent to a business opportunity

Most cause areas struggle to attract talent, because there is no money to be made. They are usually funded with philanthropic capital from a finite set of funders, and those working in such industries must often accept below-market rate salaries.

Doomer industries, on the other hand, can attract high-quality talent because they are adjacent to some underlying commercial opportunity that either makes it possible to get paid well, or attracts the overflow from workers who already made money in the adjacent field and are now in the “second act” of their careers.

Climate, AI safety, and misinformation all have this quality. Semi-relatedly, this was also the explanation I heard as to why life sciences are attractive to philanthropic funders, especially in tech – because there is an opportunity for commercialization.

Fertile environment for idea generation and exchange

Just like a warm, moist environment is perfect for bacteria to breed, a rich philosophical environment is perfect for ideas to breed in people’s minds.

Doomer industries attract ongoing media attention and speculation, moreso than “everyday disasters” like poverty, for the two reasons stated above: 1) lack of specificity or verifiability around the actual doomsday scenario, which blurs the lines between fact and fiction; and 2) adjacency to a business sector, where the presence of funding, as well as potential extreme wealth outcomes, makes these topics more exciting to write about. This attention creates a positive feedback loop for talent and funding.

Additionally, an academic or R&D component to the industry lends itself to more philosophical and ideological conversations than a pure business sector. Climate, for example, draws from not just the actual field of climatology, but adjacent industries like agriculture, manufacturing, material science, environmental science, and data. AI safety has the online forum LessWrong, as well as the para-academic Google Brain (now part of Google AI) and OpenAI for its intellectual fodder. Misinformation has the social sciences; population decline has biology, economics, genetics, and public policy.

Doomer industries as a way of allocating talent

If doomerism is the new normal, it’s unsurprising that we’d start to see “doomer industries” become a normalized way of finding meaning in one’s work. AI safety, biosecurity, misinformation, and population decline all carry the same urgency of climate, but – as Nabeel noted – appeal to different subcultures within tech. In a world with highly polarized narratives, it’s no longer enough to work on “helping the world” or “improving the world” – people need to save the world, in order to get the same high of doing meaningful work.

Applying the learnings from above, we can also imagine how doomer industries could outcompete non-doomer industries. For example, I’d guess that population decline could successfully divert talent and funding from longevity, because it has 1) an apocalyptic sense of urgency attached to it, 2) more commercial opportunities around reproductive technology, and 3) more opportunities for thought-leadering and philosophizing.

If we were to interpret doomer industries literally, it seems that they should be zero-sum: how can there be two different apocalypse scenarios happening at the same time? But, as Michael Crichton previously noted, religion is an inseparable part of human nature. If talent and funding pools don’t overlap very much [8], we ought to take a figurative interpretation of doomer industries, and simply imagine people co-existing in separate, parallel doomer universes. It is a striking example of the general sociological trend towards fragmented cultural narratives – even the end of humanity, it turns out, is a subjective experience.

Special thanks to Lyn Stoler and Anson Yu, whose feedback was indispensable.

Notes

-

Interestingly, American public opinion on whether climate change is real appears roughly unchanged since 2015, hovering around 70% of respondents who believe it is real – which is a separate question from whether people are concerned about climate change. ↩

-

A topic for another time: the correlation between New Atheism as an early 2000s movement (as well as a powerful religious right), which strongly advocated for secularism, and the portrayal of environmentalism as a secular topic. Today, I think militant secularism is less en vogue – people once again like religion and find it comforting, even if by another name – which requires discussing “religious” topics like climate differently. ↩

-

Note: My Climate Journey was a goldmine for climate career conversations, and a great resource overall. ↩

-

It’s worth noting that YPCCC did further attempt to segment its “Alarmed” group in 2021, based on levels of activity. However, the climate actions they asked about are heavily weighted towards politics and activism, which doesn’t fully encompass the range of approaches out there today. ↩

-

I toyed with the idea of whether doomer industries have anything in common with another category of work – advertising, trading, and playing (not making) video games – the first of which inspired the famous Jeff Hammerbacher quote: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.” I don’t know how exactly to connect the dots, except that all these industries seem to have that same sort of gravity well effect, but for a different crowd. ↩

-

I am not anti-social media in an ideological or politicized sense, but over time my view has only strengthened that mind-viruses are becoming more prevalent and quietly modifying our behavior, and that outside of mental health, their influence is still extremely underdiscussed. I see this as more of a scientific phenomenon (“are ideas alive?”) than an ethics question, and think it deserves more attention. ↩

-

To be fair to the popular media, Don’t Look Up was widely critiqued for its heavy-handed portrayal of climate as an extinction event, including by Eric Levitz in New York Magazine’s Intelligencer, who called it a “transparent product of its authors’ immersion in social-media echo chambers” and Kate Cohen in The Washington Post, who said that “Contrary to the movie’s implication, most Americans already believe the science on climate change. The ones who don’t…aren’t really the core problem.” ↩

-

When talent and funding do overlap between doomer industries, we see some competitiveness come out. For example, it’s probably no accident that the EA community consistently undervalues climate as a cause area, given the level of resources that are already devoted to AI safety. ↩