Reclaiming public life

January 25, 2019

In 1961, Jane Jacobs published The Death and Life of Great American Cities as a reaction to the rosy glow of 1950s urban planning policy, which she felt had become a self-serving discipline, largely divorced from reality.

Her work was a scathing critique of urban planning. She traveled around to real cities, talked to real people, observed real streets, and wrote down what she saw. Jacobs weaponized common-sense logic, proudly rooted in her experiences as a mother, journalist, and city dweller. Her findings shook up the sector, and she went on to write several more influential books about the economics of cities. [1]

While reading The Death and Life of Great American Cities, I was struck by how applicable many of her observations were to the internet today, despite being published twenty years before its invention.

One of the most useful concepts I picked up is her treatment of public and private life, which I’d like to break down in this post. We tend to think of privacy as a binary distinction, but Jacob identifies several types of public-private life which, I think, can help us think and talk about our online interactions today.

What do we mean by privacy?

I’ll start by clarifying what Jacobs doesn’t mean when we talk about privacy.

There is a literal type of privacy which implies things like lowering your blinds, shutting your door, and speaking in low whispers in order to prevent anyone from hearing you. This is not what Jacobs is interested in:

Window privacy is the easiest commodity in the world to get. You just pull down the shades or adjust the blinds. The privacy of keeping one’s personal affairs to those selected to know them, and the privacy of having reasonable control over who shall make inroads on your time and when, are rare commodities in most of this world, however, and they have nothing to do with the orientation of windows.

Privacy is about more than who can peek into your life; it’s a social norm about who should. All security systems are breakable by someone with enough desire to break them. Locking your door is less about physical security and more about the signal it’s meant to send. In the most trusting of neighborhoods, nobody locks their door at all.

The typical conversation about internet privacy today is almost exclusively concerned with technical privacy: keeping your data safe, preventing others from hacking into your stuff, addressing phishing and other social engineering scams. These technical underpinnings are essential to prevent malicious strangers from breaking into our things and ravaging our homes, but they are different from social privacy.

Social privacy is the expectation that we shouldn’t want to pry into each others’ lives. When a friend types their password into their computer, it’s expected that I look away. If someone I don’t know is working next to me at a cafe, it’s considered rude to glance at their laptop screen.

An emerging practice that highlights the tension between technical and social privacy is the resurfacing of incriminating social data from public figures - everyone from New York Times journalist Sarah Jeong to comedian Kevin Hart. The data is public. There is no technical privacy breach. But to many people, it feels transgressive to want to snoop into a stranger’s life, even if they are able to. These are the social privacy norms that Jacobs is concerned with.

Anthropologist Elena Padilla…describing Puerto Rican life in a poor and squalid district of New York…tells how it is not considered dignified for everyone to know one’s affairs. Nor is it considered dignified to snoop on others beyond the face presented in public. It does violence to a person’s privacy and rights.

Defining social privacy in an online context is difficult because it’s not clear what our “public face” really is. Unlike our physical environment, our online world contains layers of our past, present, and future selves, all occupying the same timespace. We are all time travelers, navigating multiple realities at any given moment.

How do others know when something we wrote ten years ago has passed into the shadow of our “past self”, rather than our present, public identity? Simply referencing the timestamp is not enough; some people proudly point to old blog posts written in 2005 as “the best thing I’ve ever written”.

Finding consensus on the line between present and historical data is a challenge we are still learning to navigate, but it’s important to at least recognize that this line is ambiguous, even for data that is “technically public” but “socially private”.

Why does privacy matter?

The standard argument against privacy is that if you have nothing to hide, why does it matter?

Privacy is especially important in the context of cities, or any other densely populated public life, because you’re spending a lot of time in the proximity of strangers. In a small town, everyone gets involved in each others’ affairs, because they have a high degree of trust and a low discount rate. But in a city, the default state is the reverse: low trust, high discount rate. And yet, because we spend so much time in close quarters, we have to find a way to live peaceably.

As Jacobs points out, the desire for social privacy affects everyone:

Privacy is precious in cities. It is indispensable….whether their incomes are high or their incomes are low, whether they are white or colored, whether they are old inhabitants or new, and it is a gift of great-city life deeply cherished and jealously guarded.

We accept that we are going to jostle one another and end up on top of one another and probably witness some things we didn’t want to (what urban apartment dweller hasn’t heard their neighbors coughing, yawning, shouting, or worse?), but we have an unspoken agreement to look the other way. It is the only way of maintaining order and going about our business. Furthermore, we should not be expected to defend our need for privacy:

People don’t want to invite gossip and prying into their private lives, for all sorts of reasons. They don’t want people prying into their finances, their love lives, their childrens’ lives. This is perfectly normal and expected! They simply want to be able to conduct their lives as they wish without dealing with the repercussions.

In small communities, the public-private gap is much smaller. More people know and share each others’ business, because they are invested in these relationships for a longer time, and the expected repercussions are lower. But when communities grow to the size of cities, a third form of public-private life will emerge: a hybrid phenomenon that Jacobs terms “sidewalk life”.

The value of sidewalk life

Sidewalk life is public life, but it’s one in which social privacy is respected and mutually reinforced. In Jacobs’ view, sidewalk life is one of the most important benefits of living in a city. It is not just a coping mechanism, but something that urban dwellers actively seek after.

Sidewalk life gives us access to unexpected encounters and opportunities in ways that private social gatherings do not:

The point of both the…banquet and the social life of city sidewalks is precisely that they are public. They bring together people who do not know each other in an intimate, private social fashion and in most cases do not care to know each other in that fashion.

Although urban dwellers value their privacy, this doesn’t mean they don’t want to interact with others at all. As Jacobs puts it, “if interesting, useful and significant contacts among the people of cities are confined to acquaintanceships suitable for private life, the city becomes stultified”.

Sidewalk life is a sign of a thriving urban environment. It adds variety to our lives. We like the adventures it brings, the random conversations we didn’t even know we needed. We like the idea that we can rub shoulders with strangers and come out of it all the better; it affirms our faith in humanity and makes us glad to live among unfamiliar faces.

If our smaller online communities (like private group chats or messaging threads) are our towns, social platforms (like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram) are our cities. In our urban online lives, we frequently interact with people who might not have as much context for who we are and what we’re all about.

On a public Twitter thread, for example, you often interact with people you’ve never met, and may never see again. Conversations between strangers happen entirely in public. Anyone can observe those conversations, and even join in, but there are norms around how to participate. Shouting at a stranger, or insulting their work, is considered to be in poor taste. Jumping into a conversation between two people who clearly know each other well should be treated carefully. And there’s plenty of opportunity for random, positive interactions.

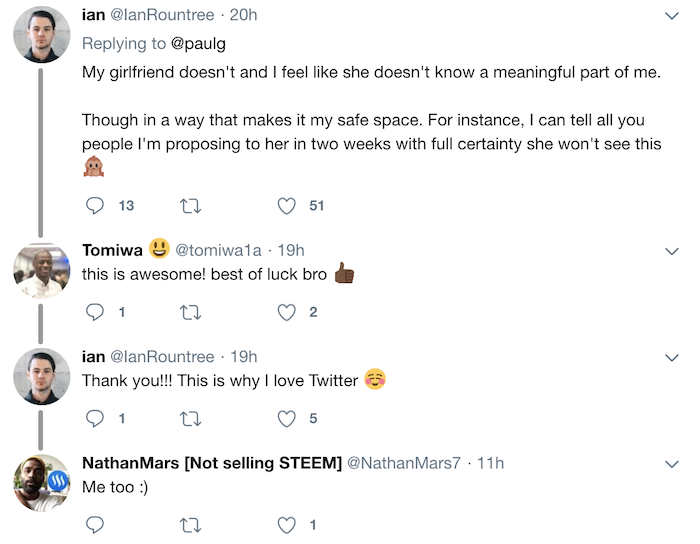

Example of a positive interaction between strangers

Example of a positive interaction between strangers

When sidewalk life thrives, we can have meaningful exchanges with strangers without the expectation that we will become intimate friends. We may interact regularly, and even feel an affinity for one another, but it’s understood that this needn’t transfer to our private lives. We don’t have to talk about our friends, parents, our deepest darkest emotions, or even where we live. If we prefer, our conversation can be confined to “sidewalk” topics, and this is what makes our public life sustainable. From Jacobs:

Under this system, it is possible in a city street neighborhood to know all kinds of people without unwelcome entanglements, without boredom, necessity for excuses, explanations, fears of giving offense…Such relationships can, and do, endure for many years, for decades; they could never have formed without that line, much less endured.

Importantly, sidewalk life has a democraticizing effect. In New York, everybody rides the MTA. Buying $3 coffee or sharing a cigarette are small luxuries that many people can afford. Although these behaviors seem small, they bring us closer to each other, benefitting not just “average” people, but the affluent, as well:

The well-off have many ways of assuaging needs for which poorer people may depend much on sidewalk life - from hearing of jobs to being recognized by the headwaiter. But nevertheless, any of the rich or near-rich in cities appear to appreciate sidewalk life as much as anybody. At any rate, they pay enormous rents to move into areas with an exuberant and varied sidewalk life.

While most interactions remain in public, sidewalk life also increases the chances of forming deeper, unexpected relationships. Without a reason to participate in sidewalk life, affluent people would just spend time in private dwellings, never to be seen on the streets.

Jacobs gives an example of how a lack of sidewalk life played out in an community organization in East Harlem, citing a woman named Mrs. Lurie, who says:

…the typical sequence is that in the course of organization leaders have found each other, gotten all involved in each others’ social lives, and have ended up talking to nobody but each others. They have not found their followers. Everything tends to degenerate into ineffective cliques, as a natural course. There is no normal public life. Just the mechanics of people learning what is going on is so difficult. It all makes the simplest social gain extra hard for these people.

Creating sidewalk life

Now that we’ve established the value of sidewalk life, how do we make it happen? What are the characteristics of a thriving public space?

Mutual trust

At the most basic level, sidewalk life cannot exist without a sense that we’re all willing to respect similar social norms. That trust is affirmed or destroyed every day by “many, many little public sidewalk contacts…most of it is ostensibly utterly trivial but the sum is not trivial at all”.

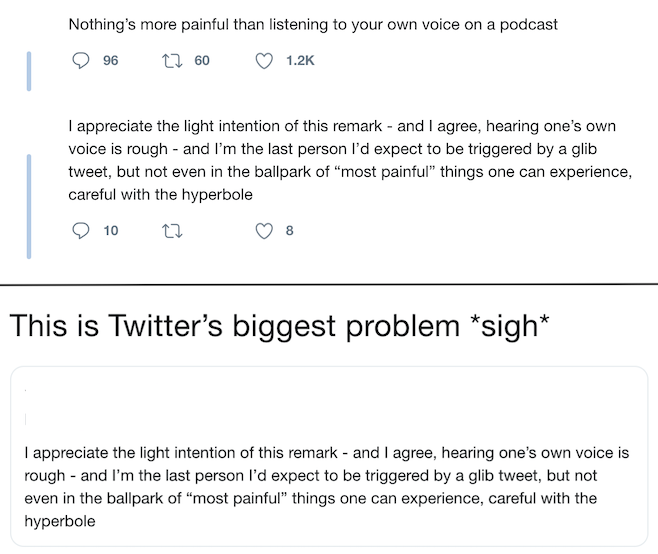

Example of a low-trust public interaction

Example of a low-trust public interaction

We should be able to assume good intentions of each other. Over time, these positive micro-interactions contribute to “a feeling for the public identity of people, a web of public respect and trust, and a resource in time of personal or neighborhood need.”

Building trust is not just about the feeling that everyone is not “out to get you”, but also respecting the need for privacy. There is a shared belief in not prying too deeply into each others’ lives. Ideally, we prioritize our desire for constructive interactions over our baser personal desires. When there is too much gossip, when strangers become too wrapped up in each others’ lives, all sense of propriety crumbles.

On a more granular level, building a healthy sidewalk life requires not just regular positive interactions, but also the presence of those who facilitate them. Jacobs calls these people public characters.

Public characters

Public characters can be thought of as the “nodes” of a social network: the central points through whom other social connections flow. They serve a few purposes: 1) being a shared point of trust among strangers, and 2) giving strangers something to gather around, which in turn strengthens our identity.

In Jacobs’ world of cities, public characters are often people like storekeepers, barkeepers, and pastors. Online, the equivalent are so-called “public figures” on social media. By thinking, talking, and interacting out in the open, these people create our public life. They give us news, ideas, information, and gossip to congregate around.

Public characters know a lot about everyone, but they don’t abuse that trust. Among all participants in the network, there’s a belief that the public character is trustworthy.

Jacobs uses the example of residents in her neighborhood leaving keys with a local deli owner, Joe Cornacchia:

Now why do I, and many others, select Joe as a logical custodian for keys? Because we trust him, first, to be a responsible custodian, but equally important because we know that he combines a feeling of good will with a feeling of no personal responsibility about our private affairs.

The ideal public character knows not to get involved in personal affairs. Jacobs gives another example of Bernie Jaffe, the owner of a local candy story, who interacts with a multitude of customers. When Jacobs asked him if he’d ever introduce his customers to each other, “He looked startled at the idea, even dismayed. ‘No,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘That would just not be advisable.’”

Jacobs goes on to explain that it has nothing to do with whether Bernie could introduce customers to each other (i.e. based on his social status in the neighborhood), but rather than he simply knows not to:

This is that almost unconsciously enforced, well-balanced line showing, the line between the city public world and the world of privacy. This line can be maintained, without awkwardness to anyone…one is free to either hang around or dash in and out, no strings attached.

The presence of people like Joe or Bernie contributes to our belief that social privacy will not be violated. Similarly, in our online worlds, we look to prominent public characters for signals as to how to conduct ourselves online. If a public character regularly divulges personal information about, or attacks, others, it encourages us to follow suit. If they refuse to engage in this sort of behavior, we, too, will emulate them.

The second aspect of public characters is that, simply put, they give us something fun to look at. Public figures on social media seem to arise out of seemingly nowhere, admired for talents as mundane as midnight cooking, playing video games, or unboxing toys. It doesn’t really matter what they do, but rather that they have provided something interesting for us to gather around. And when we find ourselves in the same location, we will also talk to one another, trade stories, and form friendships.

Not only do public figures give us information, but they also provide a place for us to discuss them: for example, the comment threads of a popular Facebook post, or quote-tweeting a popular tweet. They “spread word wholesale, in effect”, amplifying ideas to reach more people than it would have in a one-to-one game of telephone.

Finally, public characters help strengthen our identities:

In a curious way, some of these help establish an identity not only for themselves but for others. Describing the everyday life of a retired tenor at such sidewalk establishments as the restaurant and the bocce court, a San Francisco news story notes, ‘It is said of Meloni that because of his intensity, his dramatic manner and his lifelong interest in music, he transmits a feeling of vicarious importance to his many friends.’

Similarly, in our online worlds, consider the effect of Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez chopping onions on Instagram Stories, or Elon Musk smoking a joint on the Joe Rogan podcast.

Where do public characters come from? They appoint themselves. As Jacobs puts it, the only requirement is that someone be “sufficiently interested to make himself a public character”. A public character “need have no special talents or wisdom to fulfill his function…His main qualification is that he *is* public, that he talks to lots of different people.”

Localization

Finally, we need local context to make our sidewalk lives meaningful. Joe Cornacchia, the local deli owner, might be a known fixture in his neighborhood, but if he moved across town, nobody would know who he was. The street performer at a local train station is well-known to regular commuters, but means little to visitors passing through.

Although we often think of the internet as connecting us globally, it is really a composition of many small neighborhoods. Having a sense of tribe is a good thing. People often flow between those neighborhoods - just because I live in Greenwich Village doesn’t mean I can’t visit Harlem - but public characters mean the most to “their people”. A famous actor doesn’t have the same social clout among economists. Beyond a certain type of audience, public characters lose their value:

Efficiency of public sidewalk characters declines drastically if too much burden is put upon them. A store, for example, can reach a turnover in its contacts, or potential contacts, which is so large and so superficial that it is socially useless.

A life without sidewalks

When we fail to maintain a healthy sidewalk life, our public streets become unruly, and are eventually deserted. In this state, which Jacobs calls “togetherness or nothing”, we continue to share with our closest friends, but don’t participate in public life. [2]

To provide a visual metaphor, Jacobs describes a situation where children opened up a fire hydrant on the street and are destructively squirting adults with it. And yet, “nobody dared to stop them…what if you scolded or stopped them? Who would back you up over there in the blind-eyed Turf? Would you get, instead, revenge?”

While the retreat to private circles is understandable, we should treat it as a defense mechanism, not a desired outcome. Under “togetherness or nothing”, we gain the safety of our cliques at the expense of sidewalk life, with all its opportunity and adventure.

Jacobs uses Los Angeles as an example of a city with “little public life, depending mainly instead on contacts of a more private social nature”, which “lacks means for bringing together necessary ideas, necessary enthusiasms, necessary money”.

People become choosy about who they associate with, because they cannot trust just anybody anymore. Jacobs quotes her friend, Penny Kostritsky, who lives on a private street in Baltimore with little public activity, and outsiders are “rudely and pointedly ostracized”:

I have lost the advantage of living in the city without getting the advantages of living in the suburbs.…If only we had a couple of stores on the street….Then the telephone calls and the warming up and the gathering could be done naturally in public, and then people would act more decent to each other because everybody would have a right to be here.

Because there is no place for strangers to “dwell in peace together on civilized but essentially dignified and reserved terms”, a lack of sidewalk life only exacerbates differences between strangers. Private chats are a stop gap for groups of similarly-minded people, but they aren’t a sustainable solution for society as a whole. Jacobs writes:

[It] often does work well socially, if rather narrowly, for self-selected upper-middle-class people. It solves easy problems for an easy kind of population. So far as I have been able to discover, it fails to work, however, even on its own terms, with any other kind of population. The more common outcome in cities, where people are faced with the choice of sharing much or nothing, is nothing.

Reclaiming ourselves

Online, we are collectively struggling to regain our version of sidewalk life. We have lost our sense of privacy: not in the technical sense, but in the social sense. Done right, sidewalk life allows us to benefit from casual social interactions, opening the doors to unlikely friendships and opportunities.

Given the state of our public streets today, most of us head straight for the hills, confining our ideas to private conversations with trusted friends, rather than risk exposing ourselves. But fleeing our urban life for the suburbs would be a travesty. So is resigning ourselves to the chaos of the public streets where children throw rocks at cars, while we peek nervously through our blinds, afraid to say anything.

We can build better cities. We can reclaim a public life where ideas are freely shared with one another, while our need for privacy is respected. To get there, Jacobs offers a compelling framework to build an urban life that we’re proud to inhabit: one in which we can harmoniously create, learn, and discover along with friends and strangers alike.

Notes

-

Jacobs spent three years writing her book, supported by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. I’m going to claim her under the banner of independent research. ↩

-

Stephen Hawkins et al termed this the “exhausted majority” in their recent study of the American political landscape. ↩