The perks of patronage

April 9, 2019

I started a newsletter a few years ago. I added it as an afterthought to one of my blog posts with the message: “Sign up here to get updates when I post something new”. That blog post happened to blow up, so I found myself with a solid audience within a few days.

For the first two years, I thought my job was to do exactly as I promised: send updates when I publish something new. Sending email felt like an imposition, so I figured I’d better keep things brief. My early emails were basically: “Hi, here’s a thing I published, [insert random anecdote here], ok bye! Nadia”.

When I moved into full-time research last year, I decided to try a new format. I started treating newsletters like conversations, or perhaps a nice surprise package in the mail, stuffing it with a variety of treats that I thought people might find interesting. They’re much longer now: I used to try to keep my emails to a paragraph, whereas the last newsletter I sent out was nearly 1500 words.

At first I was nervous that the new format would seem too self-indulgent, or that I was being disrespectful of my subscribers’ time. Instead, not only did my unsubscribe rate drop, but current subscribers started emailing me back more often, which led to many wonderful conversations. More people shared it out with others, and my signup rate increased. Strangers now often mention it when we meet for the first time.

I used to be afraid to email people - even though they had subscribed! - because I viewed the relationship as transactional. [1] They signed up for updates, so my job was to give them updates. But it turns out that the people who followed my work didn’t really want “updates”. In fact, I’m starting to suspect that people have no idea what I actually do for a living (and I kind of like it that way!).

Patronage as taming

In Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, the prince falls in love with a flower. Eventually, he travels to another planet and realizes there are hundreds of flowers just like his. He is conflicted: does that mean his flower is less special?

The prince meets a fox, who teaches him the concept of “taming”, which he defines as “to create ties”:

‘Precisely,’ said the fox. ‘To me, you are still only a small boy, just like a hundred thousand other small boys. And I have no need of you. And you in turn have no need of me. To you, I’m just a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you shall be unique in the world. To you, I shall be unique in the world.’

We tame - that is, cultivate relationships with - others through rituals, which are regular acts that break up the day, and therefore make our lives meaningful:

‘[Rituals are] what makes one day different from the other days, one hour different from the other hours.’…‘It is the time you have wasted on your rose that makes your rose so important.’

The prince thus concludes that no matter how many identical flowers he comes across, his flower is special because he “tamed” it.

Whether it’s a newsletter, podcast, or social platform, people follow other people for reasons that are often incomprehensible, even to themselves. Somehow, your life became a ritual to them. It’s the same reason why you’ve stayed in touch with that one friend for 10 years. No matter how different your lives become, it’s “the time you’ve wasted” on each other that makes that person special to you. [2]

Rituals, like receiving a weekly newsletter in your inbox, strengthen the seemingly random bonds we feel for others. The effect becomes even more pronounced given the abundance of information available to us today. Like the prince, we are faced with a hundred flowers, and so we choose to find meaning in that flower. It’s not that I or anyone else is really that gosh darn interesting. Rather, there are so many people out there to look at, and so many people they can reach, it’s inevitable any one will be able to draw a small crowd.

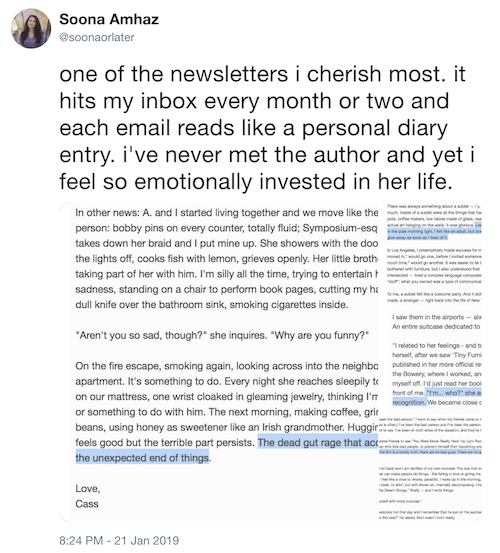

via Twitter

via Twitter

Kickstarter as original sin

The reason I thought about newsletters recently was because I got a thoughtful one from my friend Henry, a creator who’s partly funded through Patreon. Rather than sending “here’s what I did”-type Patreon updates, I’ve noticed how his updates share a more complete version of his world: from teaching coding at church, to open source work, to his favorite indie games and books he’s reading.

I notice that I have a very different relationship with the creators I fund when I get “Here’s a peek into my life” updates, vs. “Here’s some swag we promised we’d mail you” updates. With the latter, I’ll stick around until I get my stuff, and then eventually I want them to stop emailing me. With the former, I find that I’ll irrationally stick around for a long time.

It’s occasionally said that Google was the “original sin” for tech corporate culture. Every company that offers perks to its employees, knowingly or not, modeled itself after Google. Some of those perks (like parental leave or 20% time) raised the bar for the workplace. Others (like ping-pong tables and fancy snacks) became symbols of excess, frivolity, and transactional employer relationships.

I make no judgment on corporate perks (I sure enjoy mine!). The point is that Google became a blueprint for startup culture because they were the first to do it well, but we never really stopped to think about whether all of those perks made sense - whether there was actually a causal relationship between perks and quality of the workplace - or whether we were just mindlessly repeating what had been done before. [3]

Sometimes I think of Kickstarter as the original sin for modern patronage. Kickstarter, with its fundraising goals, email updates, and reward tiers, inadvertently created a blueprint for every other crowdfunding platform thereafter. But we never stopped to think about whether we repeated these behaviors because they were actually good for creators, or because that’s just how Kickstarter did it.

Reward tiers are an awkward thing for creators and their patrons. People don’t necessarily need material perks. They just want to feel close to that person. There may be transactional benefits to that relationship (ex. having access to the creator, or getting feedback on your ideas), but I think the actual underlying reasons that compel us to patronage are much less logical than that.

Patrons pay for the ritual, and the ritual tames them. These are ongoing relationships, not transactions. Creators sell intimacy to patrons. They sell “stuff” - perks - to customers.

When Kickstarter first became popular, people found it unbelievable that anyone would fund a campaign without getting equity in return. Similarly, we might find it unbelievable right now that anyone would fund someone without getting material perks in return. But I think the continued growth of personal newsletters increasingly demonstrates how that might be true.

Like any other relationship, if someone loves and cares about your work, you don’t need to bribe them to stick around. Mentors and advisors (good ones, anyway) don’t invest in people because they want to get paid. Friends (good ones, anyway) don’t hang out with you because they need something in return. They’re there because they weirdly fell in love with what you’re doing, and they want to see you succeed.

I wish we could take this as a foundational design principle when building the products, platforms, and tools that support modern patronage. I think they would look very different.

Notes

-

True story: back in 2013, when one of my first blog posts ever unexpectedly blew up on reddit, I also started a mailing list. I eventually deleted the entire list, which had a few hundred subscribers at the time, for no reason except that I was too terrified and embarrassed to send email to strangers. ↩

-

The first personal newsletter I subscribed to was a series of pseudonymous letters written by a woman named Charlotte Shane, a sex worker with a boyfriend, apparently now serialized into a book. I signed up after a friend confessed that he had found and followed her work. Neither of us knew her personally, but we were captivated by her life. I don’t remember which Kickstarter campaigns I backed that year, but I still remember getting those TinyLetters in my inbox. ↩

-

Open office layouts are another example of companies imitating what other companies do, without stopping to consider the causal relationship. ↩