Does meditation experience improve success with the jhanas?

June 27, 2024

Jhanas – a series of altered mental states that are accessed via concentration – are often described as an “advanced meditation practice,” a phrase that suggests that one must be a skilled meditator to access them: just as only a skilled outdoorsman would embark upon an expedition to the Arctic Circle. It implies that meditation exists on a spectrum of difficulty, with perhaps mindfulness apps like Calm and Headspace on one end, and jhanas on the other.

Anecdotally, however, many modern teachers notice that even experienced meditators can struggle with the jhanas, while inexperienced meditators find success. A light, playful approach seems important: it’s often said that the most effective way to access the jhanas is to not try too hard at all. While a novice backpacker should not attempt to trek to the Arctic Circle, some novice meditators appear to be quite capable of accessing the jhanas. I recently experienced this myself as a novice meditator, where the jhanas came more quickly than I had been led to believe was possible.

Is there any relationship between meditation experience and jhana success? I decided to team up with Jhourney – the company that taught me the jhanas – to answer this question. (Please note that views here are my own, and any mistakes in this piece are mine alone.)

Methodology

We looked at an anonymized sample of 81 unique participants who attended a Jhourney retreat between September 2023 and April 2024, all of whom were new to the jhanas.

Figuring out how to measure “meditation experience” was its own challenge. If we were examining differences between experienced and beginner swimmers, for example, we could approximate experience based on their lap times and effort expended. But meditation, for the most part, is a hard-to-verify skill.

Because no one metric seems to give us a complete picture of meditation experience, we decided to look at these three variables, all of which were self-reported:

- Estimated lifetime hours meditated: This is a commonly used, but not especially reliable estimate, as many people can’t precisely recall this number.

- How often (hours/week) they meditated in the 6 months leading up to the retreat: This is more helpful, but still doesn’t tell the whole story, as meditation hours can vary widely in quality, especially on- versus off-retreat. (Meditating for one hour per week for a year, for example, is different from meditating 50 hours in one week at a retreat.)

- Whether they had attended a meditation retreat before: Though not granular enough on its own, this could be a valuable data point to capture, as people who are familiar with practicing in a dedicated, structured format might progress through the jhanas more quickly.

Then we chose a few key milestones to capture how participants progressed through the jhanas during the retreat:

- Whether they experienced a jhana. Because jhanas are a highly subjective experience, we only looked at people where their descriptions matched key markers that are commonly seen across jhana self-reports.

- How far they progressed through the jhanic states, bucketed into two categories: jhanas 1-3 (which are more embodied and blissful), or jhana 4 and above (which are more mental and peaceful).

- Whether they have deterministic access to the jhanas; that is: by the end of the retreat, were they able to access the jhanas at will?

There are a few caveats to our sample. We looked at attendees across several different retreats, which employed a variety of formats, including online and in-person, as well as different teachers and programming. They also represented a mix of demographics. We were not able to control for these variables, and the margin of error is large (±8.09%, 95% CI), so we will be cautious about the conclusions we can draw from our analysis.

The difference in jhana success rates between beginner and experienced meditators is small

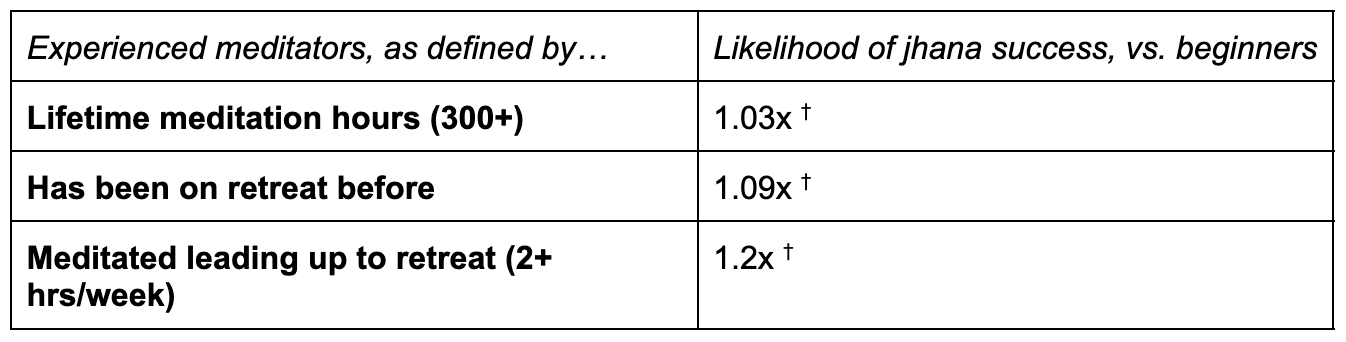

We started by looking at absolute differences in jhana success rates between experienced and beginner meditators, using our three markers of meditation experience: [1]

- For lifetime meditation hours, experienced = at or above the median in our sample (300 hours); beginner = below the median

- For “has been on retreat before,” experienced = yes; beginner = no

- For hours meditated per week, experienced = at or above the median in our sample (2 hours/week); beginner = below the median

Across all three dimensions of meditation experience, we see virtually no difference in success rates between experienced vs. beginner meditators. While the group that meditated 2+ hours/week was slightly more likely to experience a jhana, it’s worth noting that all observed differences between groups were within our margin of error.

Jhana success rates among experienced meditators, compared to beginners

† = within margin of error

† = within margin of error

Experienced meditators are more likely to progress further with the jhanas when they succeed…

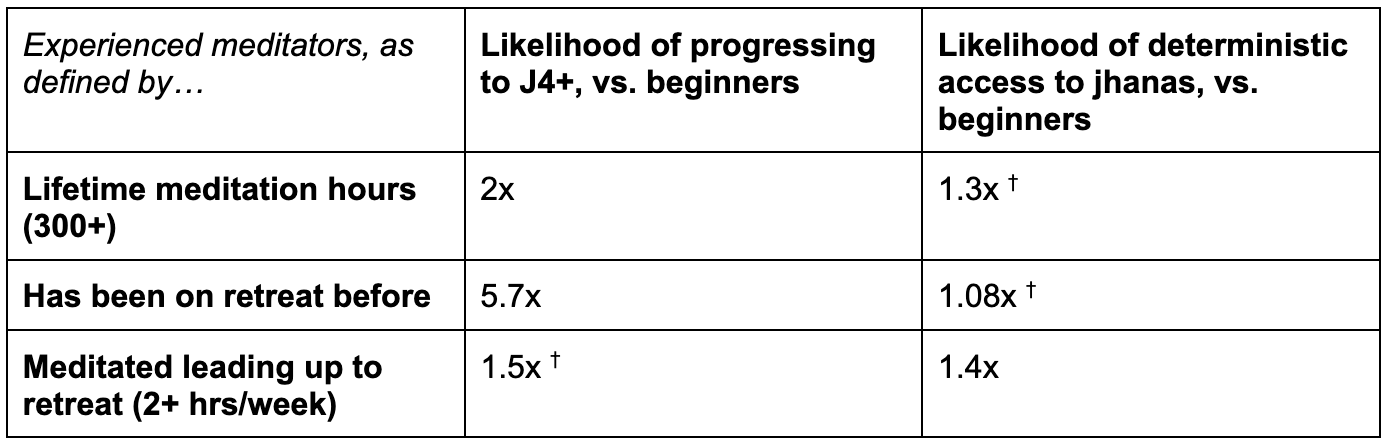

Separately, we looked at skill differences between experienced and beginner meditators who accessed the jhanas: how far they progressed, and whether they could access the jhanas deterministically by the end of the retreat. Here, the differences between groups are more pronounced.

Likelihood of jhana skill progression in experienced meditators, compared to beginners

† = within margin of error

† = within margin of error

Experienced meditators in our sample were more likely to have progressed to higher jhanic states, with the biggest difference seen among those who had attended a retreat before. They were also somewhat more likely to have gained deterministic access to the jhanas – although in this case, we saw the smallest differences between those who had attended a retreat before, versus those who had not.

It’s tempting to conclude, based on the above, that beginner meditators are just as likely to access the jhanas, but experienced meditators are more likely to progress further in their jhana skills. But the story isn’t quite that simple!

…but these differences are not attributable to meditation experience

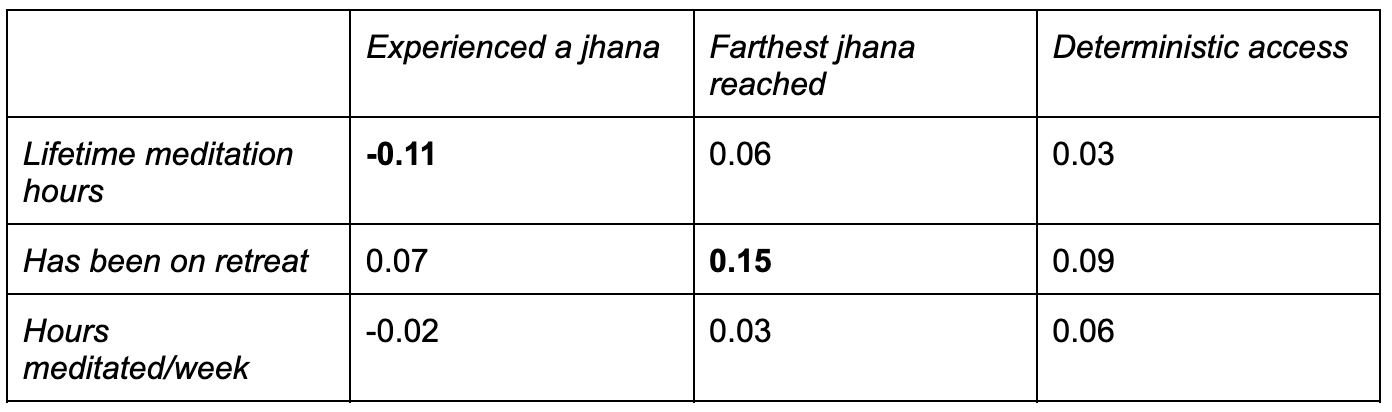

Having identified some differences between groups, we took a closer look at the data to determine whether we could establish a correlation between meditation experience and jhana skill.

Here is where we found a surprise: in our sample, we saw no significant correlations between meditation experience – no matter how it’s measured – and any jhana skill. How is this possible, given the group differences we just observed?

While beginners and experienced meditators do show differences on average, there’s a wide range of outcomes within each group. This matches the meditation teachers’ anecdotal reports, where some people – beginner or experienced – find it easy to access the jhanas, while others struggle. The variability within each group cancels out any clear pattern in the data.

Correlation coefficients: prior meditation experiences vs. jhana milestones

Our findings suggest that observed differences between groups aren’t explained by meditation experience, but by other factors that haven’t yet been identified. This presents an exciting opportunity for further research!

If not meditation experience, what predicts jhana success?

To summarize – in our sample:

- We found no significant difference in jhana success rates between experienced and beginner meditators. If this is the case, we ought to exercise caution in describing jhanas as an “advanced meditation practice,” because it could deter those who might otherwise succeed – and personally benefit – from the jhanas. “Advanced” might refer more to the consciousness-altering effects of the jhanas than the experience required to access them.

- We found no correlation between meditation experience and any jhana skill. This suggests that we either need to find more accurate ways of measuring meditation experience, or consider whether meditation experience is a (poor) proxy for some other skill that’s critical for getting into jhanas, such as an ability to sustain attention, or what’s sometimes called mental absorption. [2]

Here are a few theories we can think of as to why meditation experience doesn’t seem to impact one’s experience with the jhanas:

- We don’t have great ways of measuring (or defining!) meditation experience. What does it mean to be an “experienced” meditator, in the way that someone is an “experienced” swimmer? Number of hours meditated tells us how long someone has been practicing, but not how adept they are at cultivating and sustaining a quiet mind.

- Experienced meditators may have more confidence that they know what meditation is, so while they have assets (ex. experience sitting for long hours on retreat, or familiarity with deep levels of mental absorption), they are also at times mistaken about which skills to use and when. This misplaced confidence could lead to mixed results.

- Other types of meditation do not develop the skills needed to get into jhana. It’s possible that many popular forms of meditation (such as mindfulness, “dry insight” Vipassana, or nondual exercises) teach skills that are mechanistically different from what’s needed to get into the jhanas.

If not meditation experience, what does predict jhana success? As I’ve talked to more people about their experiences, my current hypothesis is that there are two main skills involved:

- Ability to invoke a positive feeling in the body (the initial “spark” of joy)

- Ability to sustain attention (letting the spark grow into a flame)

It seems that many of the common challenges I’ve heard about can be diagnosed as one of these two issues. For example, some people seem to fear (or “brace”) against pleasure; think they don’t deserve it; can’t come up with a source of pure, uncomplicated joy; or struggle to tap into any strong emotion at all: these are issues with invoking a positive feeling. It also explains why people sometimes report that therapy or prior psychedelic use seems to help with jhana practice.

Other practitioners struggle with anxiety; lack confidence in their abilities; get distracted or bored with practice; or strive and grasp too much. Though it may not seem obvious at first, these are issues with attention. It’s an inability to focus on the task at hand without one’s inner narrative getting in the way. The relationship between attention and emotion has been well-noted in clinical psychology, and there’s evidence to suggest that training one’s attention can improve emotional regulation.

Meditation is one method to develop better control over one’s attention, but certainly not the only one, which might be why we see mixed results among meditators – because we’re only measuring how long someone has meditated, rather than the underlying skill. Someone who practices violin for an hour a day is not necessarily proficient at the violin.

We assess a violinist’s skill by how they play music, not by how often they practice. Similarly, if we can identify and measure the skills that meditation is supposed to cultivate, it could help us more clearly diagnose and address common challenges with accessing the jhanas.

A bitter lesson for the jhanas?

In a 2019 essay, computer scientist Rich Sutton identifies a “bitter lesson” for artificial intelligence research: in the last 70 years, major progress in AI was made not by leveraging human knowledge (better models for how our brains work), but by leveraging computation (i.e. Moore’s Law, which observes that computation power doubles roughly every two years). Sutton believes that some AI researchers are misguided in their focus on developing new, complex ways of modeling the human mind, because they don’t want to admit that crude, simplistic “brute force” is actually what worked.

I wonder if there is a bitter lesson to be found for the jhanas, as well. Maybe it’s less important to unpack why you are anxious, or why you can’t seem to let yourself feel joy, or why you think you’re not good enough. Instead of introspecting heavily – trying to model where these feelings came from, and how they impact one’s behavior – it could be more effective to simply “brute force” one’s way into, for example, sparking joy and cultivating attention. With success, all the other limiting beliefs might fall away – or, perhaps, resolve themselves – in the process. [3]

As my Asterisk editor Jake Eaton wrote, while reflecting on his experience with the jhanas:

I’ve spent so much time — through therapy and self-enquiry and whatever form of analytical thought — looking for answers to questions that plague me, but when I look back at my own growth, it was never inspired by finding an answer or identifying some Freudian root. I just learned, through whatever grace, to drop the question.

Additional research, such as practitioner interviews and self-assessments, could help us better understand and validate these hypotheses, as well as surface clues on how to reliably measure and improve the skills required to successfully access, and progress through, the jhanas.

Thanks to Stephen Zerfas, Alex Gruver, and Matt Lanter.

Notes

-

We use the term “beginner” meditator in this post only as a shorthand to differentiate this group from “experienced” meditators. Experience is all relative! ↩

-

We also noticed that measuring meditation experience in different ways – lifetime hours, having attended a retreat, hours meditated per week – seemed to yield different conclusions. Strangely, however, we don’t see that one method of measurement clearly maps to consistent differences across every outcome. This could be due to the large margin of error with our sample; because different types of meditation activities influence certain outcomes more than others; or – as our findings suggest – because the causal mechanism isn’t meditation experience at all, but factors that are only partly represented by these variables. Given these inconsistencies, however, we suggest that researchers carefully consider how they measure prior meditation experience when studying the jhanas, as well as the conclusions they can draw. ↩

-

I’m reminded of the observation that if you force yourself to smile, even if you don’t feel like it, eventually, the act of smiling will boost your mood anyway. ↩