Fighting Progress

June 26, 2014

We’ve all heard the refrain, “You can’t fight progress”, in response to dialogue about the tradeoffs between technology and a healthy, balanced society.

It’s true that progress is inevitable, but advancing technology is not the sole goal for humanity.

The sole goal of humanity is to survive, which means that technological innovation must be weighed against consideration of our moral and physical limitations. Only the former keeps our numbers growing; only the latter keeps us from destroying ourselves too quickly.

There are a number of stories from recent history where we’ve intentionally backed away from innovation in order to protect the greater interests of society.

Chemical warfare was used heavily by both sides during WWI, but the effects were horrific. In 1925, the Geneva Protocol banned the use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflicts. This taboo against using chemical weapons was reinforced by the countries participating in WWII - even Hitler didn’t dare to use chemical weapons on the battlefield.

Over the following decades, the so-called “chemical taboo” grew, culminating in the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, which outlaws the production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons. 190 nations have signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, and over 80% of declared chemical weapons have now been destroyed.

We had the technology to mutilate our enemies, but we decided not to.

On a more granular level, consider food processing, which saw rapid development in a post-WWII consumer society, boosted by the Cold War space race. We learned how to package and preserve food and nutrients in entirely new ways - things already deemed disgusting by today’s standards, like canned hamburgers or canned PB&Js, and things we still enjoy today, like instant mac-n-cheese or frozen pizzas.

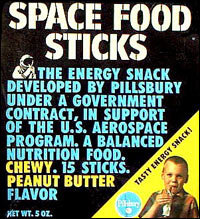

Society at the time was infatuated with food processing. The sentiment of the time was the triumph of man over nature through science, and artificial food fit right in. 1960s and 1970s science fiction is littered with references to meal replacement pills and cubes, with even Pillsbury developing and selling Space Food Sticks.

Yet, by the 1980s, we started to realize that we didn’t really want to eat artificial food all the time. In fact, the trend began moving towards slow food and local produce. We discovered there was intrinsic value, both mental and physical, in eating a meal prepared from fresh ingredients.

We had the technology to do away with food, but we decided not to.

Today, there is a surprising lack of conversation about the societal implications of big data, advertising and privacy. We love the idea of adding a data-driven curation layer onto everything. We want data to recommend to us what we should read, what we should wear, what we’re searching for online. We don’t even mind advertisers using our data to help serve us more relevant ads. “The thing that we have heard from people is that they want more targeted advertising,“ insists Facebook.

There have been some ominous rumbles from activists about the “filter bubble” and “becoming a gadget”, but even the NSA scandal couldn’t unlock a civilian uprising. And maybe that’s because we’re still in the infatuation phase, basking in the glow of a screen that knows exactly who we are and what we want, food scientists gazing blissfully upon our glorious, jiggling Jell-O molds.

Big data and quant-based advertising are less than a decade old, after all.

Maybe now is not the right time to be having that conversation about the pitfalls of sending our personal data into the aether. Maybe, as with chemical warfare and food processing, we curious humans have to make mistakes for a couple more decades first.

But maybe we should at least keep in mind some of the great “technological advancements” made in the past half-century, and how eventually we had to step back and recalibrate. Technological innovation for its own sake is meaningless without context.